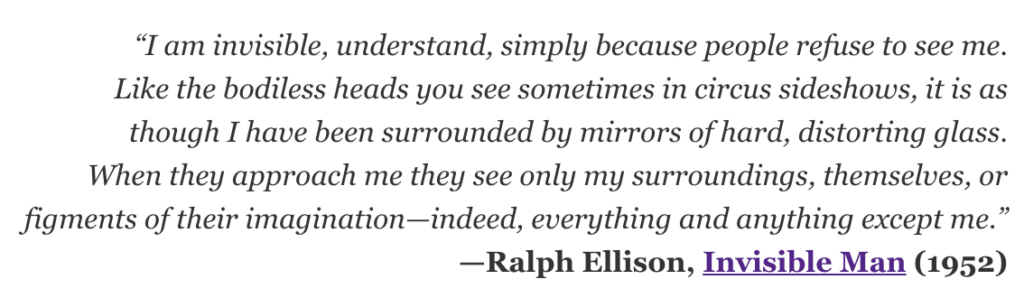

Darnell and Darnell Jr. Courtesy of Twenty Eight Ink

The first time I held

FATHERS, a stunning art book edited by Robyn Price Pierre, my heart swelled with emotion. The strength and vulnerability contained within its 423 pages moved me as a father, but also as a Black man affirmed by its intimate peek into the lives of dads in America.

I felt seen in a way I hadn’t experienced before. Flipping through its sturdy pages was like stripping away layers of caked-on stereotypes about Black fathers to reveal, as historian and writer Jelani Cobb notes in the introduction, that “our lives are more varied, our testaments more profound, our relationships deeper and more vital than the lazy beliefs projected onto us.”

I glided my hand across the smooth white cover of the four-pound book and, with my fingers, traced the outlines of its all caps black letter title—punctuated by a gold, square period.

FATHERS is a collection of photos taken primarily on the mobile phones of the men featured in its pages (or their partners) that “explores the complexities and beauty of their experiences” and “what it is to be seen—despite invisibility in American mainstream media and elsewhere,” according to Price Pierre, creative director of the publisher Twenty Eight Ink.

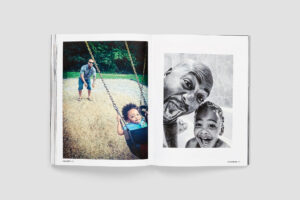

Quadean and Carter. Courtesy of Twenty Eight Ink

“Physically the book is large and heavy, purposefully designed to be weighty, to be reckoned with,” said Price Pierre, a journalist who lives in New York City. “The size and weight of the book is part of the storytelling, because it’s a statement about Black fatherhood and visibility, about not being overlooked.”

I’ve seen similar works, including the 2007 photo book “Pop: A Celebration of Black Fatherhood” by Carol Ross (which I also own), but this volume stands out. Here, the men, as co-creators with Price Pierre, frame their own narrative. Here, the images are from the personal archives of the men leaving you with the feeling of perusing a family photo album. Some include short, diary-like text to reveal the nuances of what often can’t be seen: joy, hope, fear, fragility.

For example, halfway through FATHERS, Cary is shown, head bowed, tenderly kissing the foreheads of his daughter, Meyana, and son, Macheo, as they sit on his lap:

I tell my kids all the time

that my job is to prepare them

for the day that I am no longer here.

I have taught them to be

independent at an early age

because I never know when

my time here and with them

will be up…

Vignettes like these underscore the lasting relevance of FATHERS.

Cary with Meyana and Macheo. Courtesy of Twenty Eight Ink

Released in 2018, its visual expansion of who gets to be counted in the default definition of fatherhood is as timely as ever in a moment of heightened visibility for the Black Lives Matter movement. As Cobb writes, “We know—cannot help but know—that the lives of Black men in this country end in the most arbitrary and unpredictable ways. Thus, to us the word ‘father’ connotes an act of profound optimism. Defiance.”

Perhaps this is why FATHERS feels like a conversation, one that Black dads have with one another, and within themselves. These thoughts are invisible, but FATHERS captures them on paper, crafting a tangible meditation on American ideas about Black men, Black fatherhood and, ultimately, Black families.

Fatherhood@Forty continued that conversation with Price Pierre to discuss the making and meaning of FATHERS. What follows is an edited transcript.

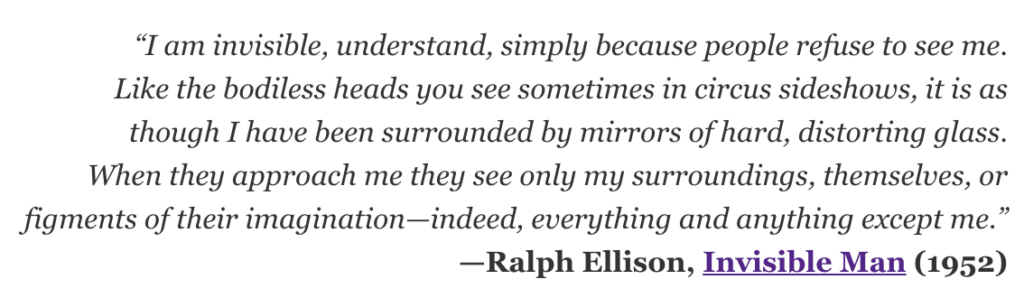

Harreld and Harreld III. Courtesy of Twenty Eight Ink

What inspired you to create FATHERS?

There were a couple of things. The first was the birth of my daughter. The first time my husband and I took her out, we were walking in Santa Monica [California] by the beach. He was pushing the stroller. We’re just walking, and I noticed the way people were interacting with us, really looking us in the eye, smiling particularly at him, almost cheering him on. It was great that people were being nice, but there was something odd about it.

I have a background in journalism, and so naturally I was curious about the response he was getting from people. I began asking some of my friends about their experience and found that they were similar. It was like Black men showing up in the world as fathers was an anomaly. And so that stuck with me.

“I wanted a space where Black fathers had the opportunity to just be. So that’s why it’s just called FATHERS, and that’s why there’s a period at the end, because it’s enough.”

After three months in Los Angeles, we came back to our apartment in New York. We live across from Central Park, so my husband would go running there after work. Every time he would leave, this fear would grip me. I knew that when he was running through the park at night, he was never going to be seen as a man who had just left his baby girl, a man who is vulnerable and loved—a man who has a home to come back to. He’s a 6’4” Black man, so I knew he could be profiled and at any moment, “fit somebody’s description.” I always held my breath until he walked back through the door.

I was also thinking a lot about Eric Garner and Tamir Rice and all of the Black death we see on the news. It’s not something we can escape. I feel like everything became heightened after my daughter was born, and I was hyper-aware of mortality. So those are some of the things I was thinking about at the time.

On a lighter note, I was taking a lot of pictures after our daughter was born in 2015. When I would scroll through my phone, I loved seeing images of them together. I love bearing witness to those small, rich moments and I wanted them to have a life outside of my phone.

And so the book manifested from all of this. Experiencing an overwhelming love while simultaneously grappling with fear.

Why an art book?

Since I was younger, I’ve always collected high fashion magazines. I’ve always collected coffee table books, and really large-form European fashion magazines. I just love what it feels like to hold something heavy and weighty in my hand with striking images. So, that was my natural aesthetic.

And I considered my resources. I knew that I could create a book, because much of that work is solitary. I didn’t have to ask for permission, pitch anyone on the idea. I could just move forward and create with little outside noise or resistance. And as a journalist and writer, I knew I could interview fathers and source images from my network, and extended network. So I just followed my curiosity and created something that could live in my home, on my coffee table, for my daughter to see.

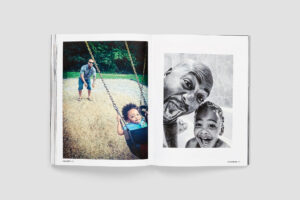

Derek and Dreyton. Courtesy of Twenty Eight Ink

How did you arrive at the title?

There were a few names I considered, but nothing felt right. I just wanted it to be really simple. Fathers was the only name that made sense to me. And then I added a period after the logo, and it felt complete. Fathers. Period. That’s it. It’s not anything more. We don’t have to self-identify at this moment as Black fathers.

“A friend who is in the book said, ‘You know, it took me a few weeks to call you or even post about it on social media because I’ve just been processing it.’ They didn’t really expect to see themselves in that way.”

For years growing up, “Vogue” had only white women in that fashion magazine, and they did not self-identify as “White Vogue.” So I wanted a space where Black fathers had the opportunity to just be. So that’s why it’s just called FATHERS, and that’s why there’s a period at the end, because it’s enough.

I noticed you didn’t mention the professions of the men. Why was that?

I was intentional about not collecting that data, because I didn’t want to distract anyone from the experience or engage in respectability politics. It wasn’t about income level. It wasn’t about what school you went to. It wasn’t about any of those things. I didn’t want to engage in that.

I knew a lot of men in the book, because I either went to school with them, or they were friends of friends. But I didn’t select anyone based of what they did for a living. Most of the men in the book are around the same age. They’re in their 30’s, 40’s, and that’s mainly because that was my network. That was in my husband’s network and [my friend] Francesca’s network. So that’s how that happened.

Kobby and Landry. Courtesy of Twenty Eight Ink

How did the men shown in the book respond to the work?

Their responses made the process worth it. One of the men called me recently, after he had watched one of the video vignettes on the Fathers Instagram page, and he shared that he hadn’t cried in years, but that hearing himself in that way brought tears to his eyes. In the vignette, he was talking about the death of his father, and the fact that they hadn’t had much of a relationship. He said it was healing.

“I would love for us to have it in our homes. I want FATHERS to live in spaces where it’s welcomed.”

After the book was released a friend who is in the book said, “You know, it took me a few weeks to call you or even post about it on social media because I’ve just been processing it.” They didn’t really expect to see themselves in that way.

My impression is that they hadn’t been asked very many questions about how they feel and what they think—which is a larger story. But sometimes I got really raw answers because it was the first time they were saying those things out loud.

And finally, most of them shared they enjoyed seeing the other fathers in the book. Being a part of a community.

Michael and Francis. Courtesy of Twenty Eight Ink

A review in the arts publication Hyperallergic contends FATHERS offers an “idealized portrait of Black fatherhood, which doesn’t provide insights into how one gets through the muck and mire of daily life to find the joy we see here.” What are your thoughts on that assessment?

Honestly, I had never considered that lens, so I was grateful for that assessment, because that’s absolutely not how I experience the book. That wasn’t my intent. As Black people, and in the case of Black fathers, I don’t know that you ever get to experience joy without some level of fear. I think there is always a duality, and that is based on our experience in this country. And so despite the smiles and loving embraces, I often experience melancholy and sadness when I look through the pages.

I was very intentional about the rhythm of the book, anchoring it with Jelani Cobb’s introduction, using images submitted by the men, and direct quotes from them. And much of what they had to say was rooted in love and fear. A specific fear that Black men face in this country. The book ends with one of those stories.

“As Black people, and in the case of Black fathers, I don’t know that you ever get to experience joy without some level of fear.”

From my experience, people don’t generally read a coffee table book from beginning to end. You experience it in moments and in parts. You don’t experience it in the same way you would a non-fiction narrative book. A lot of people, when they see FATHERS, they get this fuzzy feeling, and they experience only joy—similar to seeing my husband pushing the stroller [in Santa Monica]. I don’t experience it that way, and it’s apparent to me that there is something festering beneath the surface. And it’s quite possible I wasn’t as explicit in the book as I could or should have been, so his critique is welcomed and gives me something to consider as I embark on other projects.

Jason and Jason Jr. Courtesy of Twenty Eight Ink

In a recent Instagram post you recounted an incident in which a white woman told you she couldn’t buy FATHERS for her son because all the people in the book are Black. That reminded me of the song “F.U.B.U” (For Us By Us) on Solange’s album, “A Seat at the Table.” Sometimes there are things that we create for ourselves, and that’s okay.

Absolutely. I would love for us to have it in our homes. I want FATHERS to live in spaces where it’s welcomed. The book was inspired by my daughter, and I love that when she flips through the pages, she sees a reflection of herself.

With regard to my Instagram post, I shared that while thinking about the uprisings going on throughout the nation and the world. And the fact that so many people have had to die before people started to wake up and pay attention to what has been going on around us. To what Black people have been saying in a myriad of ways—through art, music, writing, protests, etc.

Her reaction was indicative of something larger. It wasn’t about not buying a book. It was about not buying a book because you can’t fathom not being centered in the narrative. It’s this inability to welcome Black bodies or Black thoughts or Black ideas into your space. So it’s easy to dehumanize someone when you refuse to know them. And so, here we are, yet again—in the middle of a social uprising caused by the same root problems.

Ebbie and Noey. Courtesy of Twenty Eight Ink

FATHERS is available for purchase on TheFathersBook.com for a retail price of $40.

— An edited transcript published June 16, 2020

— Feature and banner image courtesy of Twenty Eight Ink

Father on,

2564 words

Leave a Reply