Editor’s note: This post was inspired by Modern Love, the New York Times column that explores “relationships, feelings, betrayals, and revelations.” It contains passages from previously published posts.

— March 27, 2021 —

Over the past 15 years, I’ve lost and found my father several times.

I first found him in 2006, when I arrived in the lobby of a senior housing complex in Inglewood, California. There he stood, a tall, broad-shouldered man wearing bifocals and a baseball cap, waiting to greet me.

Edward was 74 at the time; I was 31. I’d last seen him when I was six years old. It was the only time I’d seen him. And it had been 25 years.

After an emotional weekend reunion, we kept in touch but with him living in California and me living 2,000 miles away in Illinois, I lost physical contact with him.

I found my father again, figuratively speaking, over a decade of casual phone calls and occasional visits that filled in the blanks of him in my mind.

A portrait emerged from stories he shared about hunting raccoons and soft-shell turtles as a young boy; his first car (“It was a raggedy ’34 Ford.”); his high school crush, Alberta (“Yeah, she was nice.”); why he joined the Navy as a young man (“I just wanted to see the world, man.”); the secret to his fried fish (“Seasoning salt in the batter.”); and his life’s regrets (“If I had liked to read, I could have amounted to something.”)

By then, I’d become a father myself to a willful little girl who between giggles, diaper changes, and tantrums taught me lessons in love, patience, and understanding. The frequency of communication dwindled with my dad, lost in the sleep-deprived haze of early fatherhood.

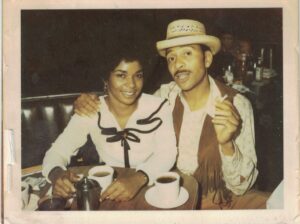

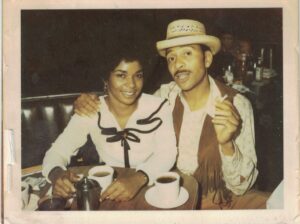

My father out on the town in his younger years.

The care and attention my dad was not around to give me as a child, is the kind I’m now providing him as his son, the caregiver.

Last October, I found my father again, amid the turmoil of the pandemic. At 89 and in declining health, he lost his balance and fell on the grounds of the same apartment complex where we had reunited after a quarter-century apart. He was taken to a hospital and discharged to a nursing home, but our family wouldn’t learn his whereabouts for ten days due to a clerical oversight: my dad neglected to leave an emergency contact on file with the property manager.

Now, as my father enters the twilight of his life, I’m preparing to lose him again and, in doing so, reckoning with the irony of it all: the care and attention my dad was not around to give me as a child, is the kind I’m now providing him as his son, the caregiver.

No sentimental love

As a new inductee of the “sandwich generation,” those thirty- and forty-somethings who are raising children while caring for aging parents, I never imagined a day would come when I could show love for my father in the same way I’ve shown for my mother, wife, and daughter. I say “show love” instead of “feel love” because sometimes love is simply the actions we take, unmoored by gushy feelings—of which I have few for my father.

Unlike many of my friends, I’ve never had a filial love for my father, mainly because he did not raise me. When his brief relationship with my mother ended, my father had no inkling she was pregnant. He wouldn’t see me in the flesh until 1981, when I was six years old and my mother took me to see him. By then she had married which meant I had a stepfather. “I thought, ‘Well, I guess you don’t need me no more,’” my dad later told me.

It didn’t help that my mother and I moved often, from one apartment to another, to escape gang-plagued neighborhoods of South-Central Los Angeles. He tried finding me in the analog decades before the internet, with no luck. (As it turned out, we never lived more than six miles away from each other.)

Given the circumstances, it’s no wonder I didn’t develop a sentimental love for my father, the kind I imagine is born of a consistent, nurturing paternal presence. Instead, I had uncles, a second stepfather, and father figures who played substitute, rounding out the fullness of familial love. That’s why it didn’t bother me as a child that my biological dad was absent.

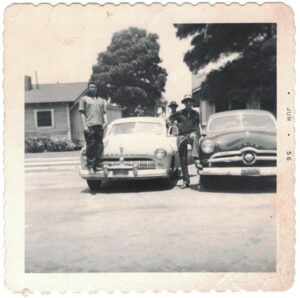

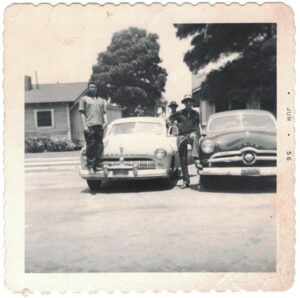

My father (right) with friends and one of his first loves—cars.

First time found

It wasn’t until I became a man that the hole in my origin story gnawed at me. I was a journalist for the Chicago Tribune then, digging up information daily about the lives of strangers, yet I couldn’t answer a seemingly simple question: Who was my father?

So I decided to investigate myself.

As I recounted in a 2006 Tribune article published on Father’s Day, this is how finding my father began:

Remembering the city where I last saw my father 25 years ago, and my mother’s single mention of his full name, I searched public records. Eight likely addresses in California emerged.

Two days after Christmas, I mailed a letter to each of them. I arrived at work a week later to a scratchy voicemail that began, ‘Johnathon, I received your letter. This is your so-called father, Edward W. Briggs.’

Goose bumps broke out on my arms. Was it really him?

A week later, I found myself on the grounds of Inglewood Meadows, a 199-unit apartment complex, in the lobby of Edward’s building, shaking his hand.

About a year after our meeting, my father sent me a shimmery Christmas card emblazoned with a sentimental declaration: “For a Special Son.” Inside the card read: “It’s hard, even at Christmas, to put into words how much happiness you’re wished, how much you’re loved, and all that it means to have a son who’s as wonderful as you. Merry Christmas.” The pre-printed text ends there, but in black ink my dad wrote in cursive, “+ Happy New Year from Dad.”

The word “dad” was in air quotes.

Chicago Tribune “Lost and Found” article from 2006.

Love as a verb

My father confessed he’s not comfortable with me calling him “dad” — he doesn’t feel he’s earned the title. Instead, he prefers if I call him by his military nickname, “Watashi,” Japanese for “I”; how his friends greet him. That’s the reality of our relationship: Edward is my father according to genetics, but he’s become my friend.

Aren’t our memories and the stories we tell about them our most valuable possessions? In that regard, my father bequeathed me a treasure trove.

I’ve equally noticed my father has a hard time saying, “I love you.” Some of this is a byproduct of his generational upbringing. But over the years, I’ve wondered if his hesitation is rooted in something deeper: a feeling of being unworthy of my compassion.

Edward lamented the fact that I’d found him in the sunset of his life, when he didn’t have much to offer in terms of money or possessions. What could an expression of “I love you” mean without the means to back it up? After all, aren’t fathers also, in part, providers? If love is an action, then what could he give me to show how much he cared? I suppose he figured he had nothing of value.

What my father failed to grasp was that I wanted something more valuable than an inheritance: time. And for the past 15 years, he’s given his freely, sharing the simple joys and painful struggles of his life.

Aren’t our memories and the stories we tell about them our most valuable possessions? In that regard, my father bequeathed me a treasure trove.

But what I, too, didn’t realize was when I said, “Love ya” after each phone call with him, there would come a day when those two words would convey more than, “I care”; they would expand to mean, “I will be there in your time of need.” Love as a verb.

FaceTime video call with my father in the COVID unit.

Nursing home awol

When my father took a fall in October, on his way to pay his rent, he never made it to the bank. Instead, he wound up in the hospital. I covered his rent for October and eventually November as his nursing home stay extended and his sister (my aunt) Linda, a gregarious, church-going woman, kept tabs on his health from Missouri; me, from Illinois.

With so many of my father’s relatives retired on fixed incomes or dealing with their own health emergencies, no one could serve as his caregiver. I stepped in. By December, I had power of attorney over his affairs—from cable bills to a cremation policy—as his thin, frail body battled chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Reports from the nursing home and Inglewood Meadows forced me and Linda to confront the reality that Edward could no longer live on his own. We spent two weeks hatching a carefully orchestrated plan dubbed “Operation Watashi” in which Linda would fly to Los Angeles and, with help from a moving company, clear out my dad’s apartment and ship his belongings to me. While there, she planned to drop by the nursing home with the hope of seeing her brother.

I laughed at the absurdity of it all: My dad, who requires oxygen and a walker to move about, had become the convalescent equivalent of Where’s Waldo.

On the day Linda landed in Los Angeles last winter, I called the nursing home to request my dad be seated by a window so his sister could visit through the glass. The receptionist informed me that wouldn’t be possible. My father had been admitted to the hospital—four days prior. No one at the nursing home had bothered to inform our family.

Once again, I was searching for my father.

I tracked him down at a hospital about eight miles north of the nursing home.

Where’s Edward?

“Did you know your dad has coronavirus?” a nurse asked when I inquired about his condition. He’d tested positive upon admission.

“No,” I said. “He was negative at the nursing home. He must have contracted it there.”

Sure enough, I later learned from the nursing home’s management company that several staff members, and subsequently patients, had been infected.

I asked to speak with my father, but the phone—our primary means of connection over the years—wasn’t working at his bedside. I asked the nurse to relay a message of love and prayers.

Linda called back two days later, only to discover he’d been transferred—yet again with no family notification. It was a bad case of déjà vu.

This time it was to the COVID unit of a nursing home, but the phone operator at the hospital could only find the name, not the address, of the facility: The Earlwood. I Googled the location and laughed at the absurdity of it all: My dad, who requires oxygen and a walker to move about, had become the convalescent equivalent of Where’s Waldo.

Three days later, I reached my dad at The Earlwood through a FaceTime video call. Miraculously, he had no symptoms of COVID and, like the survivor he is, asked how I was doing.

“Fine,” I said, “now that I’ve found you.”

Father on,

2048 words

by James

I cried all the way through. This one really hits home for me. My Dad was there even when I didn’t want him there. Now he’s gone and nothing, or no one, can replace him. And I miss my eldest Sun. We were so close while he was young. Best friends. Anyway… I am so happy for you and Watashi. I hope I get to play him in the movie and my Sun can play you. Much respect. Thanks for sharing. 🙏🏾