— June 13, 2021 —

Ever since the nation’s first Fathers’ Day was

celebrated in 1910, the “day for dads” has occasionally shared the same date as

Juneteenth, a holiday commemorating the end of slavery in the United States: June 19.

This observation ordinarily would be little more than a coincidence of the calendar. But in recent weeks with the national spotlight on the 100th anniversary of the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, the lives of my forefathers and foremothers have been at the forefront of my mind. One particular question has stood out: “What did it mean to be a newly freed Black man and a father in the American South on June 19, 1865?”

That’s the day— about two months after the Confederate general Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox, Va.—that Union Army general Gordon Granger and his troops arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas. They were charged with informing more than 250,000 enslaved Black people in the state that the Civil War had ended and they were free by an executive decree known as General Order No. 3:

“The people of Texas are informed that, in accordance with a proclamation from the Executive of the United States, all slaves are free. This involves an absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves, and the connection heretofore existing between them becomes that between employer and hired labor.”

This news triggered bewilderment as well as joyous celebrations among the newly freed Blacks, beginning what is now known as Juneteenth (short for “June Nineteenth”).

“We was all walkin’ on golden clouds….Everybody went wild…We was free. Just like that we was free,” a former slave named Felix Haywood recalled of the first celebrations, as noted in the book “Lone Star Pasts: Memory and History in Texas.” “Right off, colored folks started on the move. They seemed to want to get closer to freedom, so they’d know what it was—like it was a place or a city.”

As Blacks from Texas migrated across the country, they took Juneteenth with them. Today the holiday—also known as Freedom Day, Jubilee Day, Liberation Day, and Emancipation Day—is observed in more than 200 U.S. cities with speeches, songs, picnics, parades, and exhibits, according to the Galveston Historical Foundation.

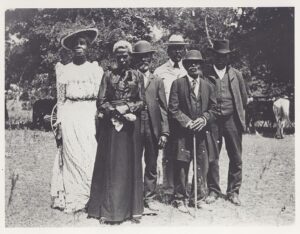

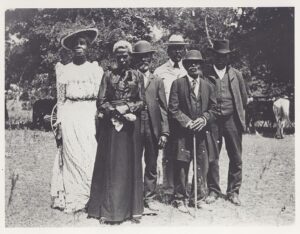

Emancipation Day Celebration, June 19, 1900 held in Texas. (Austin History Center, Austin Public Library)

“Right off, colored folks started on the move. They seemed to want to get closer to freedom, so they’d know what it was—like it was a place or a city.”—Felix Haywood

Now, you may be wondering: Didn’t the Emancipation Proclamation issued by President Abraham Lincoln free the nearly 4 million Blacks who were enslaved when the Civil War began? Not exactly.

Even though the proclamation was made effective in 1863, and declared all enslaved people in Confederate States legally free, it could not be enforced in places still under Confederate control. There’s a difference between being legally free and physically free.

“As a result, in the westernmost Confederate state of Texas, enslaved people would not be free until much later,” as explained by the National Museum of African American History and Culture. “Only through the Thirteenth Amendment did emancipation end slavery throughout the United States.”

Finding family after slavery

After they were freed, former slaves set out to reunite with family members—wives, husbands, sons, daughters, uncles, aunts, grandparents—who had been torn away by slave owners and traders. The brutality of chattel slavery meant enslaved families were forcefully separated for profit or a host of other reasons: to settle a debt, divide an estate, punish an “unruly” slave, or simply at an owner’s whim. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, “roughly half of all enslaved people were separated from their spouses and parents; about one in four of those sold were children.”

Thousands of freedmen and freedwomen wrote to the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (commonly known as the Freedmen’s Bureau) requesting assistance in locating loved ones. Others placed ads in newspapers seeking information, such as George Pearman who searched for his wife and two children with this plea in the “Daily Dispatch” (Richmond, VA) published April 24, 1867:

PERSONAL. – I wish to obtain information

in regard to my wife, SUSAN, and TWO

CHILDREN – one a girl, named NELLY, and the

other a boy, named CARTER. They formerly

belonged to Mrs. Ann Cook, of Clarke county, and I

belonged to Hugh Nelson, of the same county.

About the time General Lee’s army went into

Pennsylvania we were all brought to Richmond

and sold and separated. Any information as to

them left at the Dispatch office will be thankfully

received. GEORGE PEARMAN, Colored.

“Their will to search exemplified one of the most important personal expressions of their freedom, and it extended over many years,” historian Henry Louis Gates, Jr. notes on the website Last Seen: Finding Family After Slavery, a collaboration between the Department of History at Villanova University and Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, that features thousands of newspaper ads placed by former slaves.

“To be an involved, nurturing father was a form of resistance that was simultaneously humanizing and dehumanizing. Fatherhood imbued men with some authority, severely limited by slavery, and yet fatherhood also gave slaveholders increased leverage over a man.”—Libra Hilde

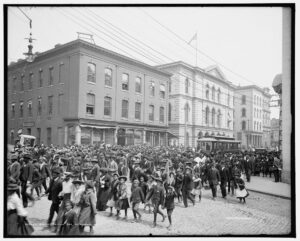

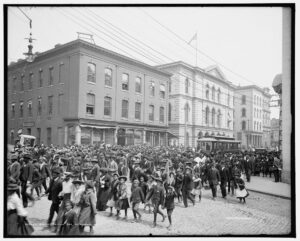

Emancipation Day in Richmond, Virginia, 1905. (Library of Congress)

In her recent book “Slavery, Fatherhood, and Paternal Duty in African American Communities over the Long Nineteenth Century,” history professor Libra Hilde shows how enslaved and then free Black fathers in the late 19th and early 20th centuries played—contrary to misconceptions of the “missing father and female matriarch”—a vital role in Black family life and their communities despite social and economic barriers erected by the dominant society.

As Hilde writes:

“Enslaved fathers faced additional agonizing contradictions. To act as caretaker deepened a man’s social connections and provided one form of human meaning, but it also further tied him to a system that eroded his humanity. To be an involved, nurturing father was a form of resistance that was simultaneously humanizing and dehumanizing. Fatherhood imbued men with some authority, severely limited by slavery, and yet fatherhood also gave slaveholders increased leverage over a man. Fathers faced intractable dilemmas. To stand up for oneself or loved ones was to risk removal from and hardship for one’s family. To be a man could mean compromising one’s sense of duty as a man, and this remained true of the African American experience in the postwar period. African Americans articulated an abiding conception of paternal duty from the antebellum period through the 1930s because they faced consistent and ongoing challenges that did not end with emancipation. Slavery and Jim Crow placed two of the central imperatives of masculinity, duty to self and duty to family, in opposition. As a result, enslaved and then free fathers found alternate, indirect, and concealed ways to support their kin, often channeling their leadership and authority through ideas and religion.”

Anaja Campbell, right, and the Denver Dancing Diamonds perform during a Juneteenth celebration parade in Denver on June 20, 2015. (Joe Amon / Denver Post via Getty Images file)

Free-ish since 1865

This year Juneteenth will arrive the same weekend as Father’s Day (June 20) and, in many ways, the challenges faced by Black Americans after the Civil War are the same faced by Black Americans today: disproportionate impoverishment, premature death, incarceration, and structural racism that cripples the collective pursuit of happiness.

In this regard, what it meant to be a newly freed Black man and a father in 1865 mirrors what it means to be a Black man and a father today: providing for and protecting your family, nurturing your children’s sense of self-worth and identity, defying stereotypes, resisting oppression, keeping the faith, and reckoning with the understanding, as Smithsonian Institution secretary Lonnie Bunch observed, that emancipation is “a process that is still unfolding—not simply a day or a moment of jubilee.”

Father on,

P.S. To learn more, check out this article by genealogist Tristan Tolman entitled, “The Effects of Slavery and Emancipation on African American Families and Family History Research” from the website Reclaiming Kin.

Credits

— Banner image: by Larry Crayton on Unsplash

— Featured image: by Reba Spike on Unsplash

1476 words

Leave a Reply