Editor’s Note: This essay is from 2016, but I’m reposting for the launch week of Fatherhood@Forty. Happy Father’s Day!

— January 12, 2016 —

Ten years ago, Friday the Thirteenth proved to be the most extraordinary day of my life.

Two days after Christmas in 2005, I set out to answer a seemingly simple question: Who was my father?

As a journalist, I wrote stories about complete strangers. But as a man, my own story was incomplete. I never knew my dad.

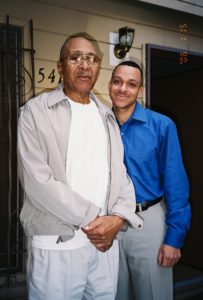

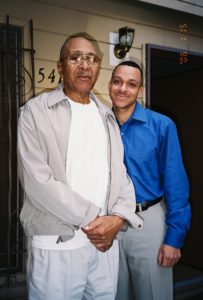

That changed on Friday, January 13, 2006. I arrived in the lobby of a senior housing complex in Inglewood, California. A tall, broad-shouldered man wearing bifocals and a baseball cap greeted me.

That man was Edward Briggs. Edward was 74; I was 31. I had last seen him when I was six years old. It was the only time I had seen him. And it had been 25 years.

Portrait of my father, Edward Briggs, taken in 2006. (Photo by Ann Johansson)

I shared the journey that led me to Edward in a Chicago Tribune article published on Father’s Day 2006 that described our initial meeting:

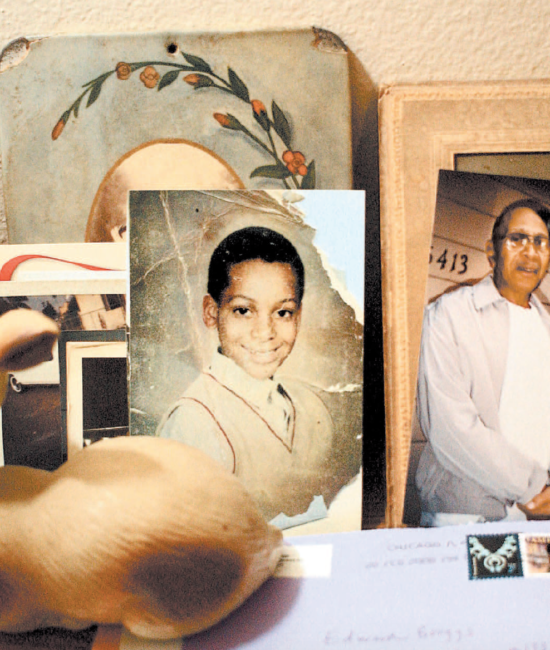

Once we were inside his apartment, he took off his cap and got out his high school yearbook, along with a batch of photos.

As we sat side by side on the sofa, close enough to feel each other’s warmth, I studied his face and body. His features seemed uncannily familiar, as though I were staring at an aged reflection of myself: oval-shaped head with lines creasing the brow; gentle brown eyes and bulb nose; salt-and-pepper, neatly trimmed mustache; smile lines carved around full lips.

Long, bony fingers wrapped in honey-toned skin extended from his palms. Our shoe sizes appeared nearly identical. The rhythm of his movements seemed to echo mine.

For 25 years Edward had been little more than a memory of light-skinned tallness. But here he was in the flesh. Here was my father?

Our striking resemblance became the elephant in the room. Neither one of us acknowledged it, but the shock was palpable. I was speechless; my father later told me that his appetite had left him.

My inbox was flooded with congratulations and compliments from readers who said the story tugged at their heartstrings and triggered tears, especially the last sentence: “On Sunday, for the first time in my 31 years, I will pick up the phone, dial his number and wish him a happy Father’s Day.”

For readers, that was the end; for me, it was the beginning. I had found my biological father, but now what?

I was under no illusion it would resemble my memories of The Cosby Show, but hoped it could blossom into something more meaningful than a good story to tell at dinner parties.

He was elderly. He lived 2,000 miles away. What kind of relationship could we realistically have? I was under no illusion it would resemble my memories of The Cosby Show, but hoped it could blossom into something more meaningful than a good story to tell at dinner parties.

When we met in 2006, my dad shared how bad he felt that I had found him in the sunset of his life, when he didn’t have much to offer in terms of money or possessions. He failed to grasp I wanted something far more valuable than an inheritance: Time. To create memories. To fill in the blanks of him in my mind. To meet his kin. Given my father’s age, I did not believe time was on our side. And yet, over the past decade, I’ve gotten to know my dad through casual phone calls and visits and also through his family — my family — a tapestry of personalities, history and legacy that I never knew I could claim.

My aunt, Rosemary (right) and her daughter, Vicky (left).

Among them are two aunts (one, Rosemary, a devout Jehovah’s Witness matriarch in Omaha who drove with me to West Des Moines, Iowa where her daughter, Vicky, shared Jim Crow-era stories about my great grandfather, Ripley Briggs; the other, Linda, a gregarious, church-going woman in Kansas City who lives near her grown daughters, Dawn, Dana and Deana); and an uncle, Jim Powell, a retired Army lieutenant colonel built like a defensive lineman, and his wife, Tommie, who before their deaths in 2013 lived for 49 years in Sacramento, where Tommie worked for the school district.

My paternal grandmother, Mamie Lue Powell.

There was a grandmother, Mamie Lue Powell, who was 96 when I met her for the first and last time at a nursing home in Grandview, Mo. Arthritis had ravaged her body and dementia had taken her once-sharp mind, but when I held her knotted-up hand in mine and stared deep into her face long enough to notice the blue rings around the iris of her eyes, she seemed glad to see me. Mamie married the late Edward Briggs Sr., my grandfather, a cab driver and quarry worker who had a penchant for fedoras and thick cigars, before getting remarried to James William Powell, a 9th and 10th Calvary Buffalo Soldier and no-nonsense man.

Edward Briggs, Sr., my paternal grandfather, a cab driver and a quarry worker.

I met two cousins, Rona and Lona. Rona is a records technician for a police department in suburban Kansas City and proud mother of three athletic sons, two of whom were featured in a humorous Sports Illustrated article about the preponderance of players named Downing on the Atchison High School basketball team. Lona is a stylish artist who by day works as a development manager for an orchestral academy in Miami Beach, Fla. By night, she designs Afrocentric dreadlock accessories, jewelry, dolls and sculptures. There is also a first cousin, once removed — Beverly, a former home child-care provider who has been married to her reverend husband, Jesse, for 56 years. In 1990, they founded the Bridge Home for Children, a residential treatment center in Kansas City for homeless, abused and neglected children. “I can’t say welcome to the family, because you have always been part of the family,” Beverly wrote in email to me. “So, instead I say to you, WELCOME HOME!”

Jim Powell, my uncle and a retired Army lieutenant colonel.

Each new family member I met was a kaleidoscope, refracting different sides of my father’s life through recollections from childhood and family reunions past. It was like that popular 1950s TV show This is Your Life in which the host would surprise guests, then take them through their lives in front of a live audience that included guest appearances by colleagues, friends and family. This is Your Life, Edward Briggs. There was only one audience member: me.

My wife and our daughter (a.k.a. Sugar Smacks).

One of the great gifts of my life in the past decade has not only been finding my father, but becoming one. My daughter was born 17 months ago — a willful little girl throbbing with her own cosmic signature. Every day, between giggles, diaper changes, tantrums and bedtime, she teaches me lessons in love, patience, and understanding

One thing I’ve learned is no man instinctively knows how to father. You become a father.

One of the great gifts of my life in the past decade has not only been finding my father, but becoming one.

For me, this process of Becoming Daddy started as soon as I learned my wife was pregnant. It gestated during 40 weeks of anticipating our daughter’s birth, the bonding with her during each week and milestone trimester, the fleeting worries and regular doctor’s visits, to say nothing of our periodic guessing game of imagining whose nose, ears and profile our daughter would favor. We were making room for an arrival — room in our home, in our thoughts, in our hearts.

That’s what it means to become a parent: You make room.

Me and my mother.

My dad missed out on becoming a father. He met my mother in 1973. They carried on a relationship for two months, maybe longer. Then, she stopped coming by his place.

“I didn’t know she was pregnant when she left. I really didn’t,” Edward told me in 2006, reflecting on the memory. In 1981, when I was 6, my mother arrived unannounced at his home — with me in tow. She was married by then but apparently felt it was important for us to meet. That was the last time I saw my dad.

When we reconnected 25 years later, Edward took those first awkward lurches toward a bond with me, those wobbly steps at becoming a father. During our first Father’s Day conversation, he shared stories about going fishing with a favorite uncle and hunting raccoons and soft-shell turtles as a young boy.

He’s since opened up about:

- Living long enough to witness the nation’s first Black president (“I couldn’t believe it. I hope he accomplishes a whole lot. It’s going to take him a while to straighten this mess out.”)

- His first car (“It was a raggedy ’34 Ford. I paid $40 for it. I traded it in and got a ’37 Studebaker.”)

- One of his high school crushes, Alberta Hunt (“Yeah, she was nice.”)

- The reason he joined the Navy as a young man (“I just wanted to see the world, man.”)

- His life’s regrets (“See my downfall was I never did like to read. If I had liked to read, I could have amounted to something.”)

- The secret to his fried fish (“Seasoning salt in the batter.”)

- And the one keepsake he treasures from his brief relationship with my mother: a fake $100 bill, play money you might find at a gag shop, signed: “I love you to the utmost. I had a wonderful time with you. Love, Sherrie.”

Nearly a year after our 2006 reunion, Edward sent me a shimmery American Greetings Christmas card emblazoned with a sentimental declaration: “For a Special Son.” The headline read, “Words can never quite convey all that our hearts would like to say.” Inside the card continued: “It’s hard, even at Christmas, to put into words how much happiness you’re wished, how much you’re loved, and all that it means to have a son who’s as wonderful as you. Merry Christmas.” The pre-printed text ends there, but in black ink my dad wrote in cursive, “+ Happy New Year from Dad.” The word dad was in air quotes. I understand why.

Edward and me.

Edward’s confessed he’s not comfortable being “Dad” — he doesn’t feel he’s earned the title. Instead, he prefers if I call him by his military nickname, “Watashi,” Japanese for “I”; that’s how his friends greet him. That’s the reality of our relationship: Edward is my father solely on the basis of genetics, but he’s become my friend.

See, my family loved me so much that I never felt the void of my father so much as the holes in my own story.

As I wrote in 2006, “I had a full family — my mother, grandmother, uncles and, later, stepfathers, all of whom played substitute. They were the ones who got the wrapped gifts, bear hugs and handmade cards scribbled in crayon with ‘I love you.’” As a result, I don’t mind calling Edward dad even though he will never be that for me.

See, my family loved me so much that I never felt the void of my father so much as the holes in my own story.

That acceptance frees me from expectations. Over the years, my aunt Linda has scolded her brother Edward for not picking up the phone to call me more often, for not remembering my birthday or sending cards and letters. “You went through all that trouble to find him,” Linda once said to me in a huff. “He should call you more often.” At times I have wished my dad would reach out more, but that’s not the relationship we have.

There is no textbook way for a man to “make room” for his grown son.

In getting to know my dad, I’ve come to admire him for being a survivor. He’s survived a war, stomach cancer, a stroke. Not even a car accident that left him with a slight limp slowed his swagger — he found a walking cane to match his Stacy Adams ensemble and kept it moving. It’s no wonder then that on the walls of my father’s apartment hang portraits of Jesus and Martin Luther King, Jr. — faith and conviction.

For years, my mother never asked about my motive for finding Edward or even acknowledged that he was part of my life. But in the fall of October 2011, when she learned I planned to visit Edward to see how well he was recovering from a stroke, she handed me a get-well card to give to him. I discovered afterward she included a note inside with her cell phone number and they later spoke. A month later, during Thanksgiving weekend in Chicago, my mother — perhaps triggered by the framed copy of the 2006 “Lost and Found” Tribune article hanging in the hallway — asked, “Why did you want to find Edward?” To which I replied, “Because I wanted to know my story.” She looked pensive in the wake of my response.

Me, my daughter and Edward.

In finding and befriending my father, I remain thankful to my mother for raising me to be the kind of man bold enough to break cycles — the cycles of blame and shame, the heritage of not knowing our parents, our history, ourselves.

January the 13th will come and go, and each time it does I reflect on this lasting lesson. If you want to know the answers to life’s most pressing questions, you have to venture out into the world and find them for yourself.

This essay was honored with a Communicator Award of Distinction for writing in 2016 by the Academy of Interactive & Visual Arts.

2413 words

3 responses