— July 30, 2023 —

I stepped into my father’s hospital room knowing it would be the last time I’d see him alive.

Thin and frail at 92, he was hospitalized eight days earlier with pneumonia and a collapsed lung. These ailments were the last things his battered body needed. For more than a decade, it had withstood the withering effects of COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), but was on its last legs.

Two days before I arrived, a nurse called to share an unsettling update: My father, Edward, kept pulling out his feeding tube and removing his oxygen mask. In one instance, he mustered enough breath to utter his intent: “I just want to die.”

This news was saddening but not surprising.

Ever since my dad, weakened by a bout of pneumonia, lost his balance and fell on the grounds of his apartment complex in 2020, he’s been dying a little bit each day. For the past three years, instead of coming and going as he pleased, he’s lived in a nursing home where his declining health rendered him bed-ridden and in need of long-term care.

Now he was simply tired of being alive.

And so, I boarded a flight to Los Angeles from Chicago on a mission of mercy: to set my father free.

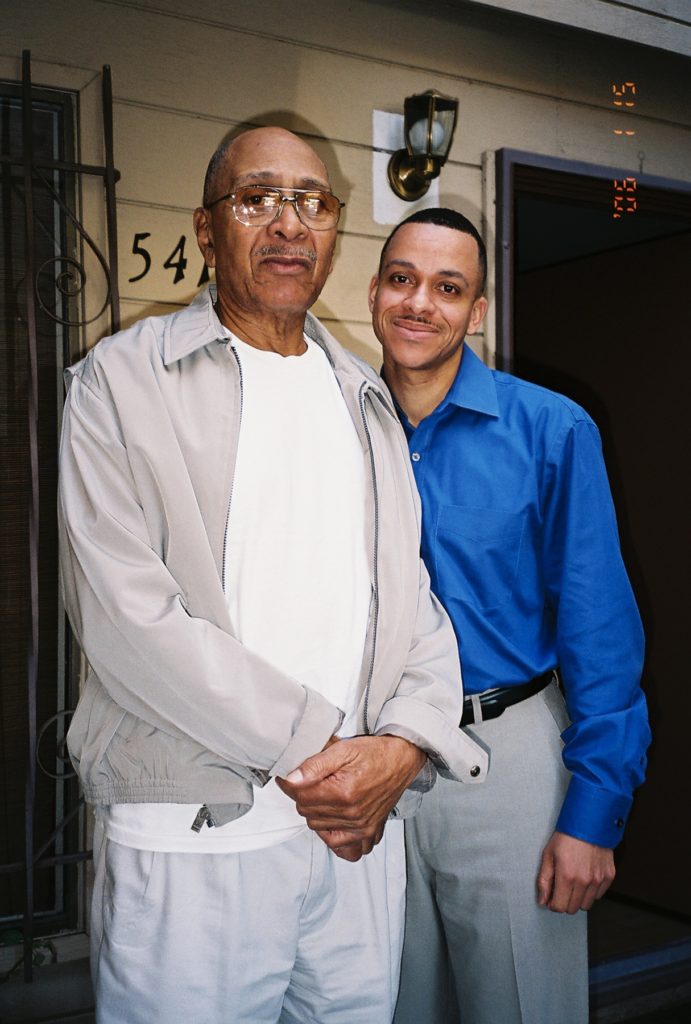

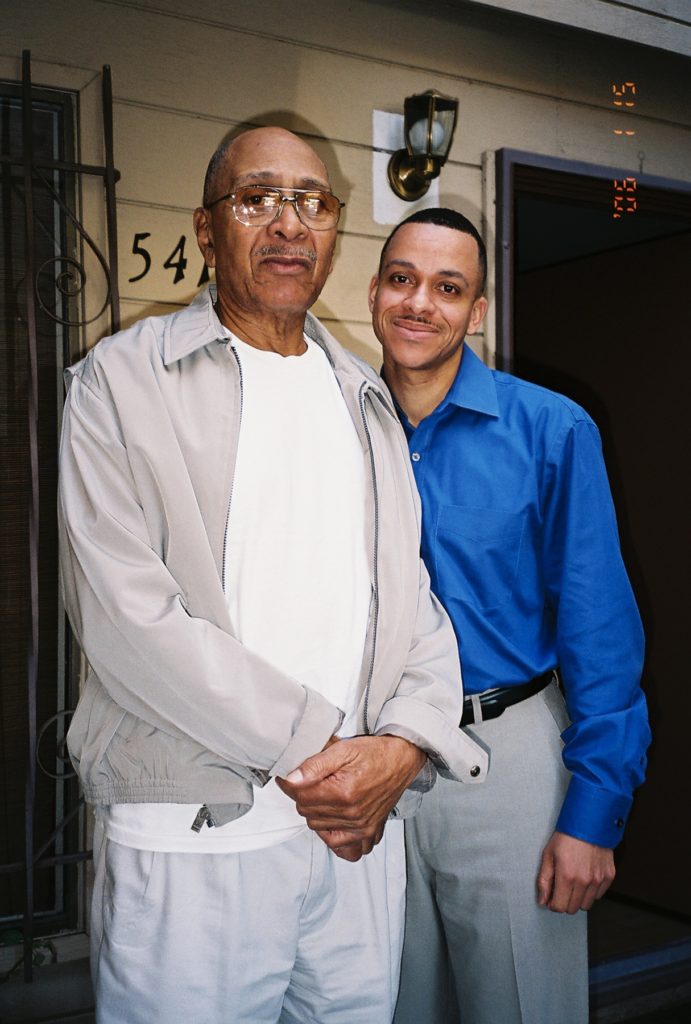

My father, Edward, in his home in 2006. Photo by Ann Johansson

My father, Edward, in his home in 2006. Photo by Ann JohanssonComfort Care

After seven hours of travel, I found myself on the third floor of a hospital in Culver City, Calif., gazing down at Edward in his bed. He laid so still and rigid beneath the blankets that it felt like staring into a coffin.

He was surrounded by tubes, wires, and screens. To his right, an IV supplied fluids, antibiotics, and nutrients through a vein. A vital signs monitor tracked his blood pressure, oxygen saturation, and respiratory and heart rates. To his left, a high-flow nasal apparatus supplied oxygen from a compact tank to a see-through face mask fastened over his nose and mouth. The hiss and mechanical clank of pressurized oxygen permeated the room like a soundtrack befitting Darth Vader.

My dad’s gentle brown eyes were open when I arrived, but he appeared to drift in and out of consciousness. I couldn’t tell if he registered my presence, so I pulled back the blankets to place my right hand on top of his, gently squeezing until I could feel his knuckles beneath my palm.

The path to this last goodbye began in 2005, when I set out to answer a seemingly simple question: Who was my father?

“The nurse told me what you said the other day,” I said to him. “I know you’re tired of fighting. If you can hear me, just know that we love you and that it’s okay to let go.”

Moments later I met with the hospital’s palliative care coordinator to update my dad’s end-of-life care plan. To honor his wishes, a check mark was placed next to two boxes. The first read “Do Not Attempt Resuscitation/CPR (Allow Natural Death)”; the second, “Comfort-Focused Treatment – relieve pain and suffering with medication by any route as needed.”

Within an hour or so my dad was given a morphine drip to ease his pain. Twenty minutes later, his high-flow oxygen mask was removed, replaced by a less forceful version. No one on the medical team could estimate how long he’d survive without high-flow. He might endure only minutes, perhaps hours, or conceivably even days. His sister (my aunt) Linda summed it up this way: “It’s God’s date and time.”

Fateful Decisions

As I watched his vital signs fluctuate, I thought about the arc of our relationship and how a decision I made 18 years ago to find my biological father had lead me to this moment, sitting in chair at his bedside, praying for his soul to be at peace.

The path to this last goodbye began in 2005, when I set out to answer a seemingly simple question: Who was my father?

I was a journalist at the time and often found myself more familiar with the intimate details of strangers’ families than my own. This was largely due to the absence of my father from my life, leaving me with questions that remained unanswered. Who was he? How did he meet my mother? Is he still alive?

Remembering the city where I last saw him, and my mother’s single mention of his full name, I searched public records. Eight likely addresses in California emerged. Two days after Christmas, I mailed a letter to each one. It read, in part:

I apologize for the randomness of this letter, but I’m looking for my biological father whose name was given to me as Edward Willard Briggs. I’ve written to every address in California listed to Edward W. Briggs with the hope that I reach a family member, spouse, or friend with information about his whereabouts, assuming he is alive.

I arrived at work a week later to a scratchy voicemail that began, “Johnathon, I received your letter. This is your so-called father, Edward W. Briggs.” My arms erupted in goosebumps. Could it truly be him?

On Friday, January 13, 2006, I stepped into the lobby of a senior housing complex in Inglewood, Calif. There he stood, a tall, broad-shouldered man wearing bifocals and a baseball cap, waiting to greet me.

Edward was 74 at the time; I was 31. I’d last seen him when I was six years old. It was the only time I’d seen him. And it had been 25 years.

My father didn’t have to respond to my letter, but he did. He wanted to be found. And because of that decision we reconnected, each taking those first awkward lurches toward getting to know one another.

Me and Edward in 2006.

Me and Edward in 2006.Practical Bonds

My father was born in 1931 in Atchison, Kan., to Edward “Eddie” Briggs and Mamie Lue Jones (later Powell), but was mostly raised by a maternal grandmother and aunt. The first of nine children, he graduated in 1950 from Atchison High School where he sang in chorus, excelled in basketball and track, and served as treasurer of the Hi-Y club.

Edward went on to attend Kansas Vocational School in Topeka before he was drafted into the Korean War. He received an honorable discharge from the U.S. Navy in 1954. Asked why he chose that military branch, he told me: “I just wanted to see the world, man.”

My father didn’t have to respond to my letter, but he did. He wanted to be found.

After disembarking in San Francisco, Edward settled in Los Angeles where an uncle lived and eventually found work at a foundry, Turner Casting Corporation, as a metalworker. He was working there in 1973 when he met my mother, Sherry, one day as she waited for a bus. He retired from Turner Casting in 1991, after 25 years of service, but his original dream was to employ his smooth tenor voice as a professional singer.

As I recounted in 2016, our relationship was practical, not sentimental:

My father confessed he’s not comfortable with me calling him “dad”—he doesn’t feel he’s earned the title. Instead, he prefers if I call him by his military nickname, “Watashi,” Japanese for “I”; how his friends greet him. That’s the reality of our relationship: Edward is my father according to genetics, but he’s become my friend.

In fact, I’m one of Watashi’s last living friends. After nine decades on earth, he’s simply outlived nearly everyone he’s ever known. His mother and father, two common-law wives, a brother in Sacramento, Calif., a sister in Omaha, Neb., his lady friend Arline McNeal, his good friend James Newton, his Navy buddies, and just about all his West Coast relatives.

Yet here I am, his only child, the last person in his world to help him transition from this life to the next.

I believe Watashi had a hunch it might turn out this way. After I became his power of attorney in 2020, I came across a payoff letter for his pre-arranged cremation. On a related policy document, he used Wite-Out to erase the name of a nephew in San Diego as the contingent beneficiary and filled in my contact information. In the field labeled “Relationship,” he scribbled “Son.”

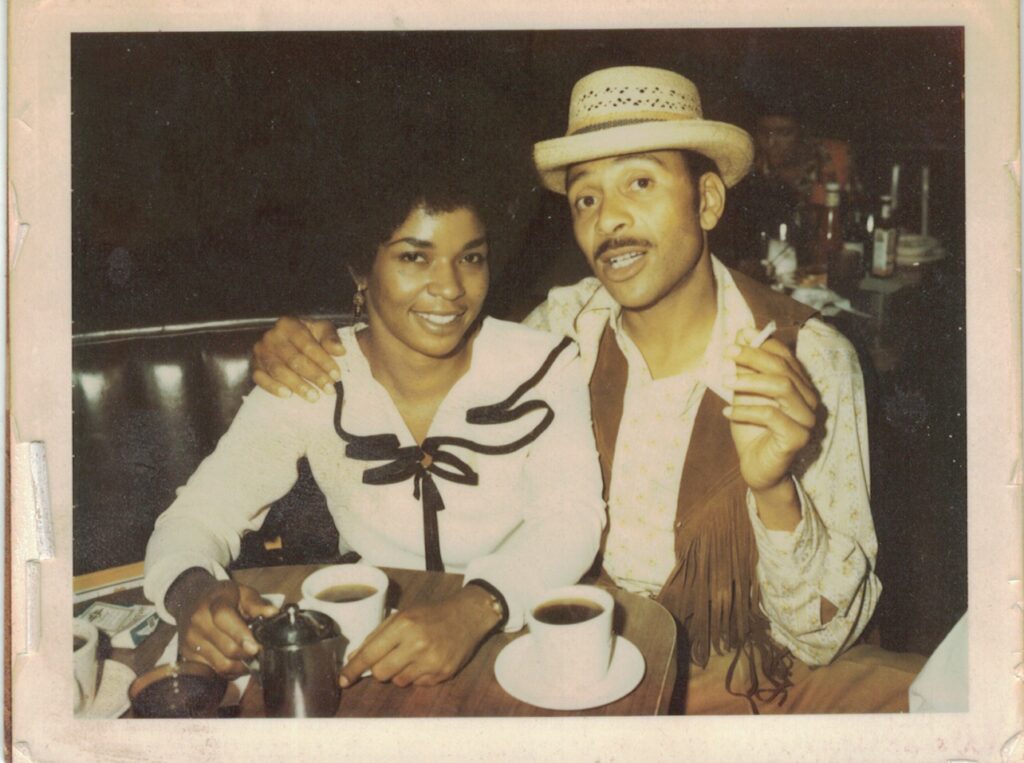

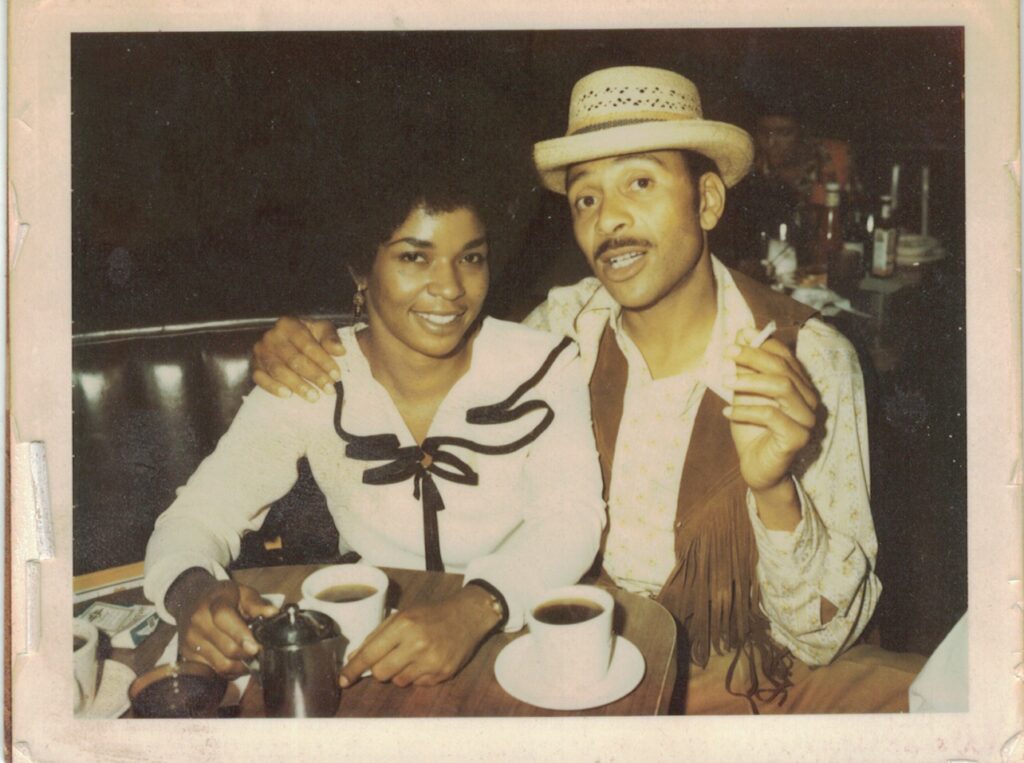

My father out on the town in his younger years.

My father out on the town in his younger years.Three Faiths

Before Edward received the morphine drip, I called my mother to let her know I was in Los Angeles, as I always do. When she learned the reason for my visit, she said, “I’m so glad you’re there to help Edward’s spirit make a peaceful transition.” Her heartfelt words made me think about the three faith traditions present in my family.

We have Jehovah’s Witnesses who believe that when a person dies, they cease to exist. There is not an immortal soul that survives when the body dies.

We have Christians who believe each person possesses a soul that leaves the body at death and goes to an afterlife in Heaven or Hell.

And we have Buddhists who believe that consciousness (the spirit) continues after death and may be reborn. Death is not a tragic ending. It’s a beautiful beginning.

My mother, who is Buddhist, encouraged me to take deep breaths—in the midst of medical decisions and mortuary paperwork and the surreal nature of it all—to center myself and share these last breaths in the room with Edward.

Finding Peace

On and off, over the course of nearly six hours, as the afternoon turned to evening and the periodic beeps of distress sensors suggested my father’s imminent demise, I did just that. Edward never uttered a word to me, but occasionally turned his head to stare in my direction. He knew I was there.

Eased by the effects of morphine, his body relaxed and his vital signs appeared to stabilize. Along the way, the medical team reduced him to just two nasal prongs. Finally, I could see the fullness of my father’s face, no longer obscured by masks or tubes or pain.

I stood at his bedside, one last time, and held his hand.

“I have to go now, Watashi, but I’m glad I got the chance to see you. Thank you for responding to my letter all those years ago. These last 17 years have meant so much to me.” My eyes swelled with tears.

Two days later, my dad was discharged from the hospital to hospice care at his nursing home.

Four days after that, a chaplain visited to pray for him and read psalms from the Bible.

Today, July 30, 2023, Edward died peacefully in his room.

It is a beautiful beginning.

Survivors & Memorial Services

Edward is survived by a son, Johnathon E. Briggs (wife Rhonda Briggs) of Naperville, Ill.; the mother of his son, Dianna S. Pennyjelly (formerly Sherry Larry) of Los Angeles; a brother, Gary W. Powell of Kansas City, Mo.; two sisters, Linda M. Harbin of Kansas City, Mo. and Anna M. Kelley of Atchinson, Kan.; a granddaughter, Emarie Briggs, and a host of nieces, nephews, and cousins.

He was preceded in death by his parents; brothers James W. Powell of Sacramento, Calif.; Richard W. Powell of Salt Lake City, Utah; and Gilbert C. Powell of Kansas City, Mo.; sisters Loretta L. Whiting of San Diego, Calif. and Rosemary Skipper of Omaha, Neb.

A burial at sea is being arranged. No memorial service is immediately planned. Details of a future service will be published on this memorial blog post when the time comes.

Additional Stories

I’ve chronicled my relationship with Watashi over the years through a series of essays:

— Banner image by Dan Meyers on Unsplash

— Feature image by Ann Johansson

2035 words

by Carl

Great Display of Love for Your Dad. Much Love – CW

by Johnathon E. Briggs

Thanks for the kind words, Carl. I hope all is well with you and yours.