— April 19, 2020 —

Amid the sobering data that shows the coronavirus is infecting and

killing black Americans at disproportionately high rates across the country, I see the lives of black fathers cut short. Like mighty oaks and young saplings being leveled in a forest, the virus has taken down proud patriarchs who anchored generations and mid-life dads of young children.

The fallen span all walks of life from jazz pianist Ellis Marsalis, 85, the family patriarch who nurtured four musician sons to prominence, including Wynton and Branford Marsalis, to 43-year-old Marlowe Stoudamire, an entrepreneur and influential civic booster for Detroit who leaves behind a wife and two young children.

Stoudamire reportedly had none of the underlying health conditions such as diabetes, chronic lung disease, and heart disease that experts say increase the risk of dying from COVID-19, the disease caused by the newly discovered coronavirus.

Those illnesses are often referred to as “pre-existing conditions,” a now ubiquitous term that was the subject of conversation between Oprah Winfrey and CNN commentator Van Jones during her recent special “Oprah Talks COVID-19,” a series of conversations with experts and ordinary people.

To be clear, a pre-existing condition is often defined as a medical illness or injury you had before you enrolled in a new health care plan. That could include asthma, diabetes, cancer, kidney disease, and even obesity. But the true pre-existing condition fueling the high death toll of African Americans from COVID-19 is something less visible, but just as real: structural violence.

That’s the term Norwegian sociologist Johan Galtung and liberation theologians used in the 1960s to describe how social institutions systemically harm people by preventing them from meeting their basic needs and reaching their full potential. I first learned of Galtung’s work while pursuing my master’s degree in public health.

The pre-existing condition fueling the high death toll of African Americans from COVID-19 is something less visible, but just as real: structural violence.

The word “violence” often conjures images of physical force, but Galtung used it to describe the social structures—economic, political, legal, religious, and cultural—that order our world. These structures turn violent, Galtung explained, when they cause injury to people by lowering “the actual degree to which someone is able to meet their needs below that which would otherwise be possible.”

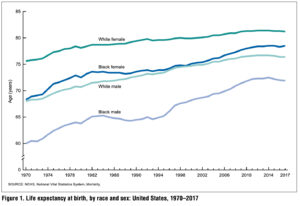

Institutionalized racism, sexism, and ageism are just a few examples of structural violence. So are segregation and poverty in the form of unemployment, lack of education, healthcare, food, and shelter that has led to the racial health disparities that exist today. It’s no wonder African Americans, on average, have the lowest life expectancy of any racial or ethnic group in the country.

It turns out that Existing While Black is a stressful pre-existing condition.

New York Times staff writer and 1619 Project founder Nikole Hannah-Jones underscored this fact when she told Oprah that “man-made racial inequality” is driving the disparity in COVID-19 deaths. In Chicago alone, African Americans are 30 percent of the population, but account for 52 percent of COVID-19 cases citywide and 72 percent of deaths, according to city data.

“What we hear is, ‘Black people are more likely to have asthma. Black people are more likely to have hypertension.’ But these conditions didn’t come out of thin air. It’s not that black people are making bad lifestyle choices, it’s that we know that black people are disproportionately in neighborhoods next to toxic waste sites and highways, which is why we have such high asthma rates,” Hannah-Jones said. “We know that black people are the most segregated of all racial groups, which means we are in neighborhoods that don’t have access to fresh quality food, which leads to hypertension. This is the type of created, man-made environment that black people are suffering from right now.”

Historical Perspective

These conditions didn’t happen overnight. That’s something Joseph Harrington, who served as an assistant commissioner at the Chicago Department of Public Health and as the regional health officer for Cook County for the Illinois Department of Public Health, felt compelled to remind his social media followers last week after hearing historically inaccurate statements from public officials.

“Many of them have stated that African Americans have had to face or deal with disparities in health for decades, when the real answer is centuries,” Harrington said in a post shared on Facebook and LinkedIn. “National Negro Health Week began 105 years ago in April of 1915, in response to disturbing findings by the Tuskegee Institute that highlighted the poor health status of African Americans in the early part of the 20th Century. At a session of the Tuskegee Negro Conference in 1914, founder of the Tuskegee Institute, Booker T. Washington presented data, which showed the economic costs of the poor health status of the black population in the United States.”

“Some believed that African Americans simply did not have the capacity to understand disease, infection, and treatment. Such conclusions led doctors to debate the utility of providing African Americans with even basic health education…”—Paul Braff

Harrington then shared an excerpt from a recent article in the American Journal of the Public Health written by Paul Braff, a Ph.D. candidate at Temple University whose research focuses on African American history and public health during the 20th century:

“In the early 20th century, like today, African Americans had poorer health than their White counterparts. However, the health discrepancy was more pronounced. The laws of the Jim Crow South combined with less formal hiring and residential restrictions in the North to confine the majority of African Americans to the lowest-paid jobs and the worst, most crowded accommodations. Such conditions contributed to African Americans suffering from, and dying at, a higher rate than Whites for almost all diseases. The crude death rate in the United States in 1900 was 17.2 deaths per 1000 people, but the African American rate was 25.

In addition, the average life expectancy in the early 1900s was 49.2 years, but that of African Americans was only 35 years. In the South, where the vast majority of African Americans lived, researchers found that 450,000 African Americans were seriously ill at any given time and that 45% of those illnesses, such as tuberculosis and pneumonia, were preventable with basic health education.

Problematically, many White physicians thought like the anonymous doctor who said, “You might as well try to teach sanitation to mules as to try to teach it to the negroes.” Some believed that African Americans simply did not have the capacity to understand disease, infection, and treatment. Such conclusions led doctors to debate the utility of providing African Americans with even basic health education, such as lectures on disease and sex. And because of racial exclusions at many medical schools, there were few African American physicians to contradict these conclusions. The African American-doctor to-African American-patient ratio in the early 20th century was 1:3,000, as opposed to 1:700 for White doctors and patients, and whereas African American physicians primarily practiced in cities, most African Americans lived in rural areas.”

Speaking on the racial toll of the virus, civil rights activist Rev. Jesse Jackson summed it up this way to the Associated Press: “It’s America’s unfinished business—we’re free, but not equal. There’s a reality check that has been brought by the coronavirus, that exposes the weakness and the opportunity.”

Mask Up and Live

In Chicago, where I once worked as a journalist, I was heartened to see the launch of the “Mask Up and Live” campaign, the brainchild of creative Caliph Rasul (of Rascal By Design), health advocate Carlos Meyers (of the non-profit Beyond Care) and technologist Walid Johnson (of startup United NFC)—all black men, most fathers, directly impacted by COVID-19. The campaign aims to educate African Americans on the deadly impact of the coronavirus with an ambitious goal of giving away a million masks in underserved communities.

“Black men are taking charge to ensure we are taking care of our communities,” said Illinois state representative LaShawn Ford, who helped kick off the campaign last week along with Chicago rapper Twista and Creative Scott, owner of Creative Salon. “We intend to get masks out to those who don’t have access to them.”

The focus on individual and community actions to combat COVID-19 is necessary but not sufficient to end the present-day harm of structural violence. To do that, we must pursue systemic solutions with the same level of urgency that we now seek a vaccine.

This is a fact the pandemic has revealed, one we can mask no longer.

Father on,

1498 words

2 responses